From December 2024 to March of this year, I re-listened to the audiobooks of every single book in the series, A Series of Unfortunate Events, by Lemony Snicket. For those of you who weren’t bookish children in the 1990s-2000s, the series follows three children: the Baudelaire siblings, narrated by “Lemony Snicket”, an omniscient narrator who follows the Baudelaire’s every move.

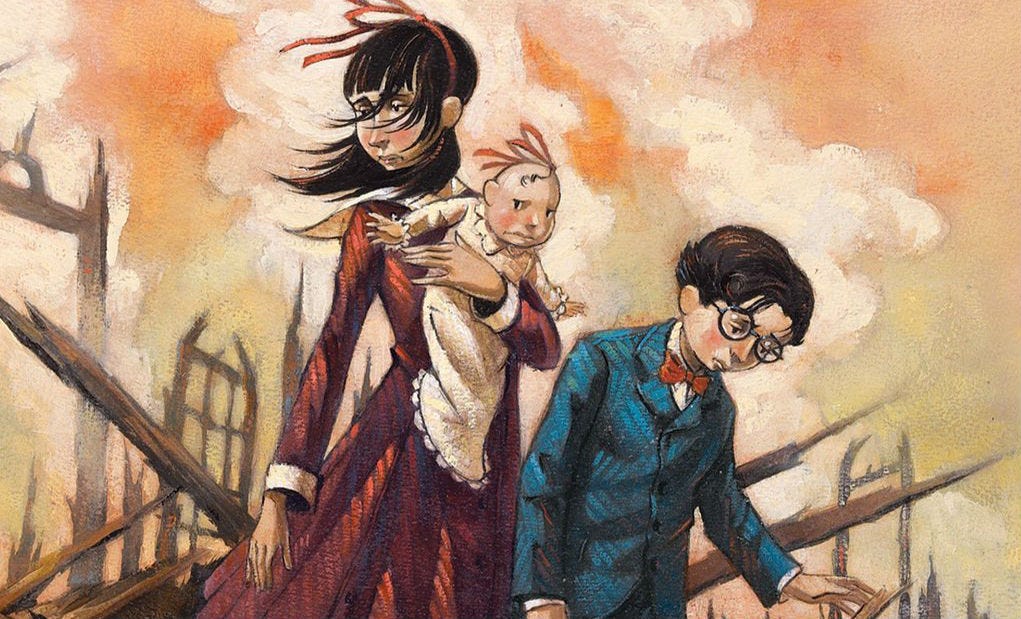

What makes these books so unfortunate? On page 8 of the very first book of the series, The Bad Beginning, the three children learn they have been orphaned by a fire that killed both their parents and destroyed their home. Straight away, we’re launched into a Edward Gorey-esque, quasi-Edwardian, gothic world. Now orphans, the Baudelaires are sent to live with the cruel and villainous Count Olaf who only wants them for the fortune their parents left behind.

From there, each book has a reliable formula: the children move into their new home and adjust to life with their new guardian, the evil Count Olaf shows up in disguise to try and kidnap them, the children expose Olaf and he disappears before the police can show up. Each story ends as the children are taken away from their current home.

This pattern breaks towards the end of the fifth book. The Baudelaires discover their parents were members of a secret organisation known as “V.F.D.” - the membership of which seems to be the reason they were killed in the fire. Lemony Snicket treats us to numerous secrets and red herrings - other versions of V.F.D. pop up in Baudelaires search, including “very fancy doilies”, “village of fowl devotees”, “volunteer feline detectives” and “verbal fridge dialogue”. Lemony also continually references a sugar bowl that he and “Beatrice” - an unidentified woman to whom each book is dedicated1 - stole many years ago. So who killed the Baudelaire’s parents? Why? What is the sugar bowl? Why did they steal it? Why was so important? What was inside it?

Snicket never tells us. Some mysteries are resolved, but many are abandoned with no answer other than the one the reader creates. I believe that’s the exact reason that 29-year-old me, a full 20 years since the last book was published, is still absorbed by these books. I will forever admire how Snicket had the opportunity to create a perfect mystery series where every single clue fit perfectly in place and instead decided to end it with readers asking more questions than they went in with.

This decision, however, perfectly fits the grander narrative of the books. The series touches on themes such as the mistreatment of workers under capitalism2 , the danger of literal interpretation of the law3, the role of charity4 and, more generally, what is ethical in the face of evil5. In other words: the orphans encounter societal structures they, and the reader, assume will protect them and, time and time again, they don’t.

Throughout the books, adults are cruel, lazy, selfish and don’t listen to children. The central villain is not the obviously cruel Count Olaf, but the systems that fail the children. The banker who is put in charge of finding them a home never ensures they are safe and happy. Guardians ignore or fail to notice when Count Olaf has shown up and is threatening the children’s lives. Even V.F.D, the organisation their parents upheld, is riddled with people who do evil things in the name of “honour”.6

The Baudelaires are shocked, out of nowhere, by their parents death and, across the thirteen books, they never recover from this. In fact, the articulation of this loss is one of the best descriptions of grief I have ever read:

‘It is like walking up the stairs to your bedroom in the dark, and thinking there is one more stair than there is. Your foot falls down, through the air, and there is a sickly moment of dark surprise as you try and readjust the way you thought of things.’

There are a scattering of references to classic detectives in the series - The Moonstone by Wilkie Collins, Edgar Allan Poe’s C. Auguste Dupine, The Murder of Roger Ackroyd by Agatha Christie. Yet, this series is completely unlike the mystery genres it alludes to. Every Poirot mystery ends with Poirot assembling every key figure into a room, pointing at them one by one to explain their role in the mystery and what the real and true answer is. Every clue is explained, every loose end is tied up. This works perfectly for the world that Poirot lives in.

In the second last book The Penultimate Peril, Lemony Snicket even plays with the idea of what this kind of ending would look like in his series. The Baudelaires, Count Olaf, and all the previous guardians and characters the Baudelaires have met assemble at the Hotel Denouement where the guardians decide the best thing to do is put Count Olaf on trial. The book seems set to reveal every secret, to lock Count Olaf up forever, to find the perfect home for the Baudelaires. But of course, it doesn’t. The judges panel has been rigged and the adults refuse to listen to Baudelaires when they point this out. There’s a whole other book to go, where readers are whiplashed from a busy hotel to a remote island, and very few questions are answered.

A classic Poirot or detective denouement doesn’t work for these books, because the Baudelaires, live in a different world - the world where Edwardian and 50s noir aesthetics match, and there are secret organisations that use jars of pickles and poems as clues, where a baby can have her own language where “Busheney” means an evil man7. More importantly, the Baudelaires live in the world where their parents have died. Their grief is always unresolved and, in life in general, many things are never sewn up neatly.

If books help us make sense of the world, A Series of Unfortunate Events helps us make sense of the fact that life isn’t fair, that the people you thought of as perfect were flawed and capable of great immorality, that bad things happen to good people and that the world isn’t as safe as you were brought up to hope it would be. Perhaps, most of all, it prepares us for something uglier - the fact that closure is never guaranteed. No matter what we want, we may never get it. No matter what we lose, we might never find it again. No matter who dies, that wound may never heal. Or, as Lemony says: ‘The sad truth is the truth is sad.’

Lemony Snick is clearly loved Beatrice, but the feeling wasn’t requited. This is a nice literary reference to Charles Baudelaire’s poem “La Béatrice” and the first clue that Beatrice was, in fact, the Baudelaire’s mother.

The Miserable Mill (book four): the Baudelaires work in a highly dangerous mill that pays all of its workers in chewing gum and coupons

The Bad Beginning (book one): Count Olaf attempts to legally marry Violet, the eldest Baudelaire, so he can acquire the Baudelaire fortune

The Hostile Hospital (book eight): the Baudelaires work for a charity that sings to sick people in hospital, but refuses to actually help them when they’re in need because it’s “too depressing”

Throughout the books the Baudelaires repeatedly have to decide whether it is moral to do something immoral to a villainous person in order to stop them from hurting other people.

There’s genuinely a plotline in the book about if it’s ethical to create bioweapons that threaten the entire human race!

I see what you did there Lemony Snicket.