I’ve spoken before about the reading and thinking I’ve been doing about trees. In a previous post I wrote about the tree in Jane Eyre, and the way it symbolises the duality in the romantic and horrifying gothic narrative in the story between Rochester and Jane.

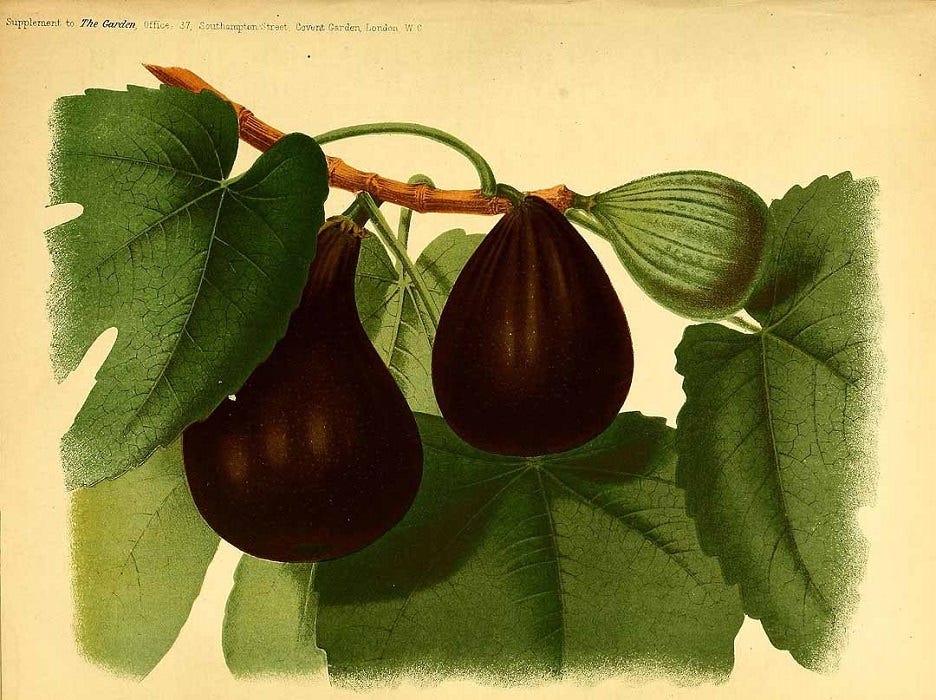

Many other trees follow me: real, imagined, photographed. Another fictional tree that has its roots firmly around my feet is the fig tree featured in Sylvia Plath’s novel The Bell Jar. The famous quote is from the perspective of Esther, the protagonist, and focuses on her overwhelming indecision about her life.

“I saw my life branching out before me like the green fig tree in the story. From the tip of every branch, like a fat purple fig, a wonderful future beckoned and winked. One fig was a husband and a happy home and children, and another fig was a brilliant professor and another fig was Ee Gee, the amazing editor, and another fig was Europe and Africa and South America, and another fig was Constantin and Socrates and Attila and a pack of other lovers with queer names and offbeat professions, and another fig was an Olympic lady crew champion, and beyond and above these figs were many more figs that I couldn’t quite make out. I saw myself sitting in the crotch of this fig tree, starving to death, just because I couldn’t make up my mind which of the figs I would choose. I wanted each and every one of them, but choosing one meant losing all the rest, and, as I sat there, unable to decide, the figs began to wrinkle and go black, and, one by one, they plopped to the ground at my feet.”

Sylvia Plath’s work is mostly analysed purely through her mental health and death by suicide - in fact, The Bell Jar is often called a roman à clef because it’s believed to be a thinly veiled autobiography. Understanding her poems and stories only through this lens is like trying to understand an entire book by only reading a couple pages. Throughout her career, Plath also wrote fiercely about the joys of swimming and animals, her children and nature. She kept a track of her food through diaries, letters and poems which is now serialised through a Twitter account

“dance, dinner, cocktails, art exhibit, drive”

(14th April, 1954)

and

“I filled up on four good pieces of bread, butter, and jam which satisfied me for the time.”

(1947)

When tackling the fig tree, it’s easy to focus on the indecision, the figs that die and fall to the ground, but what takes me in is how much Esther wants to do with her life. Even in her depression, she is overwhelmed by how much life has to offer. Life isn’t misery and emptiness - the sadness is in not being able to access what happiness and fulfilment it has on offer.

The cruellest thing about our lives aren’t that they’re short, but that we don’t get a second go. If I could take more turns, I know I’d use them to do more travel, read more books, write more but also all the things I want to do but don’t always have time or funds for: learn more languages, paint, sew and draw, cook and bake, live abroad. I love my life very much, but who can resist that niggling thought of what if? Imagine all the other jobs I could do, parties I could go to, people I could meet.

At some point, you realise that having a good life means actually saying no to things that you do want to do, because saying yes to all of them means you cannot do all of them justice. To continue Plath’s analogy: if you filled your fridge with all the figs, you’re either going to make yourself very sick of figs, or some of them are going to rot.

For women, especially, I think this metaphor can really resonate because of this idea of “the woman who has it all”. The perfect mother who has a high-flying career, a perfect marriage, a big group of friends, immaculate clothes, fulfilling hobbies and a toned body. This image sets women up to fail, and the fig tree can offer a way to talk about all the things women both want and are told to do and how grabbing all of them means others rot. (Side note: can you tell I’m in my late 20s and doing some serious thinking about what I want from life?)

However, Charlotte’s Ahlin’s article on the fig tree from Bustle points out that the fig tree quote is often used entirely out of context. Only a couple of pages after the fig tree, we are told that Esther sits down and eats:

“I don’t know what I ate, but I felt immensely better after the first mouthful. It occurred to me that my vision of the fig tree and all the fat figs that withered and fell to earth might well have arisen from the profound void of an empty stomach.”

She was hungry for life, but also she was just physically hungry. In other words, our lives feel the most out of control when we can’t get through everyday actions. Esther’s inability to decide what she wants from life is because she’s in an emotional and physical state where she’s unable to sleep, eat and live. Of course she can’t make huge decisions: she can’t even make small ones. As Charlotte Anhlin says:

“the withering fig tree [is not] the inevitable end to all young people […] Esther’s fears are valid, but the book is not about her succumbing to fear. It’s about her slowly, steadily finding her feet again, one sandwich at a time.”

In short, we are not doomed to pick one path (or fig) that will always ultimately feel unsatisfying. It’s more about how every choice looks good when you don’t have anything. How hard it is to make big life plans when the day-to-day is impossible.

Plath’s fig tree gives me some sense of hope for other reasons. It might sound flippant, but figs are also delicious. For me, they are a symbol of summer - ripe, slightly sweet and decadent (best served with other lavish things - good cheese, good wine, good bread, balsamic vinegar, salted almonds and honey). Esther’s fig tree is also a symbol of hope, in a way, because whilst she can’t see a way to any of these futures or dreams, she still has the capacity to imagine them.

My wider love for trees (real and fictional) is because of how much joy they give me. My experience with nature is very rarely bold hill-walking or adventuring, but much more every day walks to the woods or the park. There, the trees still hold so much: blossom, flowers, birds, bugs and bees. When I write at my desk, I often stare out the window thinking and staring directly at the same tree, and the magpies that live in it. It’s no coincidence, to me, that Plath’s metaphor about the paralysis of depression has a vibrant, living being at the heart of it, ripe with life and something delicious, waiting to be savoured.

In other words, let’s use Sylvia’s to see us out. Here’s some lines from “Blackberrying”, a poem also about fruit - about how endings don’t keep us from savouring something sweet. Death could be waiting for us, but so too could be abundance -

“Nobody in the lane, and nothing, nothing but blackberries, Blackberries on either side, though on the right mainly, A blackberry alley, going down in hooks, and a sea Somewhere at the end of it, heaving. Blackberries Big as the ball of my thumb, and dumb as eyes Ebon in the hedges, fat With blue-red juices. [...] I come to one bush of berries so ripe it is a bush of flies, Hanging their bluegreen bellies and their wing panes in a Chinese screen. The honey-feast of the berries has stunned them; they believe in heaven.”

(from “Blackberrying” by Sylvia Plath)

With gratitude to the following publications:

“This Quote From 'The Bell Jar' Is Always Used Out-Of-Context & It Changes The Whole Meaning” by Charlotte Ahlin for Bustle

“‘Food is good … I’m bound to eat & eat.’ Discovering Sylvia Plath’s (Digital) Food Diary” by Ella Marley for Lula

Ariel by Sylvia Plath published by Faber & Faber

“Blackberrying” by Sylvia Plath on Poetry Foundation website

Letters Home: Correspondence 1950-1963 by Sylvia Plath, edited Aurelia Plath published by Faber & Faber

The Bell Jar by Sylvia Plath published by Faber & Faber

“Poetry and Food” by the Editors of the Poetry Foundation website