You’ve probably seen the Lascaux paintings. They are one of, if not the, most famous examples of cave painting - estimated to be up to 17,000 years old. As a concept, “cave paintings” bear a huge weight. They’re brought up as the example in every conversation about the value of art. They’re the shortcut example of humans always making art, even in survival situation. They teach us about the stories people told, the pigments teach us about the plants and materials they found or traded.

More recently, people have written at length about how the painters depict humans alongside, instead of dominating, animals and nature - something we could all learn from these days. Feminist scholars have theorised that some of these paintings use counting systems to track women’s menstrual cycles.

Today’s story isn’t about the Lascaux cave paintings. It’s about how they were found.

On September 12th, 1940, a eighteen-year-old Marcel Ravidat was walking his dog through the woods of Montignac, a town in southwest France. He was on a break from studying to be a mechanic. In some retellings his dog began sniffing around the hole, in others Robot went down (or fell) into them.

I’ll now give you a moment to process the fact that one of the most important human artefacts of all time was found because of a dog called Robot.

ROBOT!

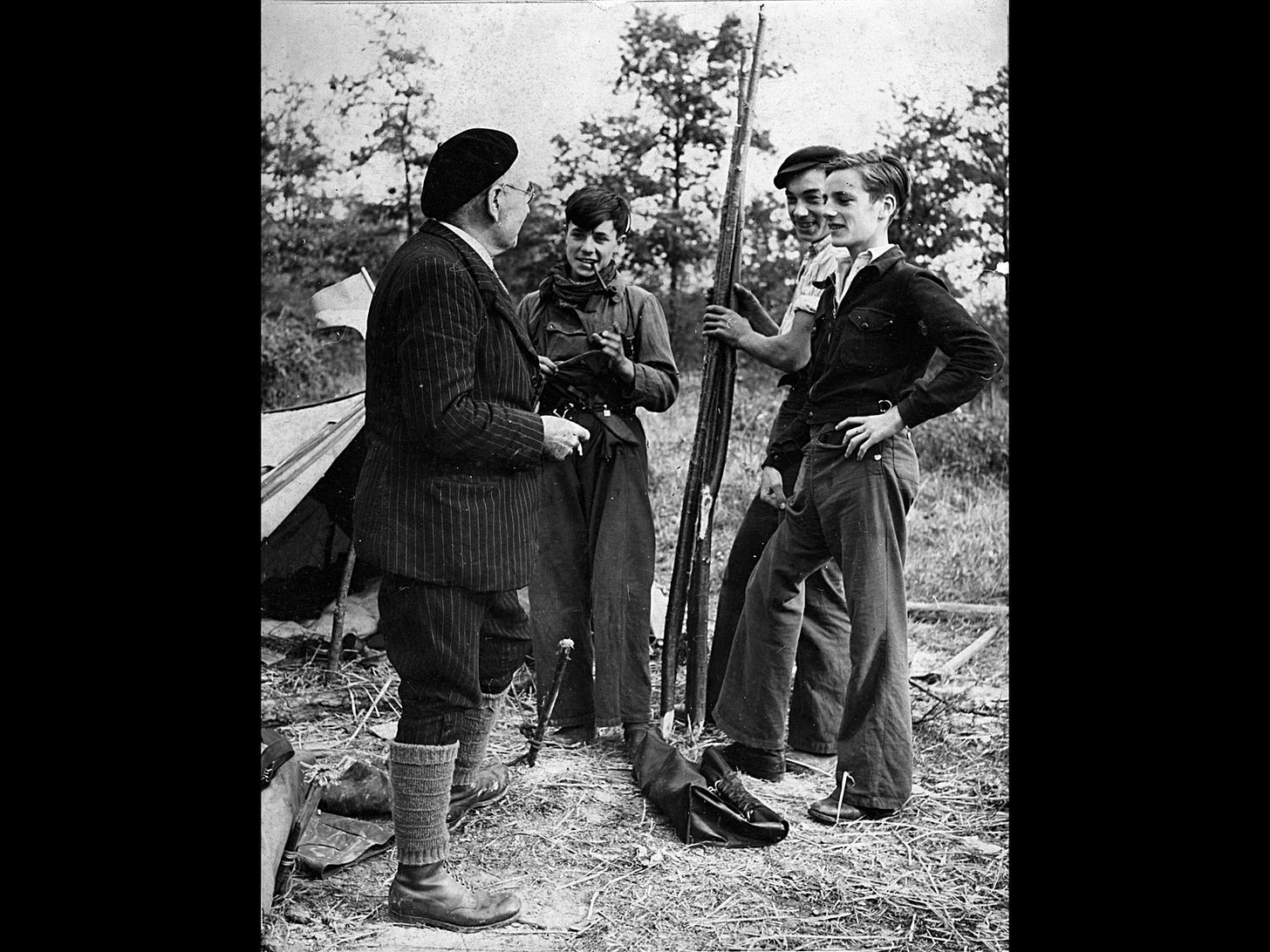

Marcel fetched three friends - Jacques Marsal, Georges Agnel and Simon Coencas - who took an oil lamp down into the cavern, sliding the 15m down the hole. They explored until their oil lamps ran out, deciding they’d visit the next day - but not before they all swore to keep the site a secret.

The boys didn’t really know what they’d found at that point, so they spoke to their school teacher, Leon Laval, who, on visiting the site, immediately saw how significant this find was. He urged the boys to prevent anyone from touching or vandalising the paintings.

The fate of these paintings was pretty precarious - it was the middle of World War II and the Nazis had captured Paris. The kind of infrastructure that protects and supports sites like Lascaux was in tatters and there was most likely a fear about drawing the Nazis attention to this discovery.

When Leon Laval told his pupils to look after the paintings, they took it seriously. 14-year-old Jacques Marsal camped outside the cavern to protect it at all times.

Years ago, in a film-writing class, a tutor told me stories that revolve around trying to find, or be reunited, with an item were now unrealistic.

“It’s so easy to buy a replacement for things like that now,” he said. “How far would you really go to try and get something you’d lost?”

At the time I had freshly read (and cried over) Donna Tartt’s The Goldfinch, a doorstop novel which follows a young boy throughout his life as he tries to keep, find, and take care of Het Puttertje after he steals it from a museum. It is a beautiful book and reading it made me so sure that humans will go to great lengths of discomfort, pain, even face death, to protect an object that has value to them.

In other words, it makes me think of a stanza from a poem by Ada Limón which runs:

“When the plane went down in San Francisco,

I thought of my friend M. He’s obsessed with plane crashes.

He memorizes the wrecked metal details,

the clear cool skies cut by black scars of smoke.

Once, while driving, he told me about all the crashes:

The one in blue Kentucky, in yellow Iowa.

How people go on, and how people don’t.

It was almost a year before I learned

that his brother was a pilot.

I can’t help it.

I love the way men love.”

From “Accident Report in the Tall, Tall Weeds”, Bright Dead Things.

Since 1963, access to Lascaux has been limited to scientists who protect the paintings. This was due to damage from the carbon dioxide visitors were breathing out into the caves. Collectively, there has been a decision that this art must be kept safe, even if that means we can’t see them.

Marcel Ravidat, Jacques Marsal, Georges Agnel and Simon Coenca didn’t have that consensus or support behind them. They just had an oil lamp and a sense of duty handed down from a trusted teacher.

In 1986, the four men who found the cave reunited. They’d lost contact with each other during the war. At one point Simon Coenca, who was Jewish, spent a month in Drancy internment camp. Every September 12th since that reunion, they have continued to meet. Only two are still alive.

Until 1989, when he died, Jacques Marsal stayed on as “The Guardian of Lascaux”. Whilst it was still open, he acted as a guide. When it closed, he continued to guard the site.

When we talk about these paintings, let’s not just talk about what the creation of them says about us - but what the protection says too. When I think of what art means to us, I could think of a hundred different books, poems, stories, paintings, plays, films or moments I have cherished. But these days, I imagine a 14-year-old boy sleeping outside a cave, with nothing by his conviction and wonder keeping him company.

Like Ada Limón, I can’t help but love the way he loves.